- News & Reviews

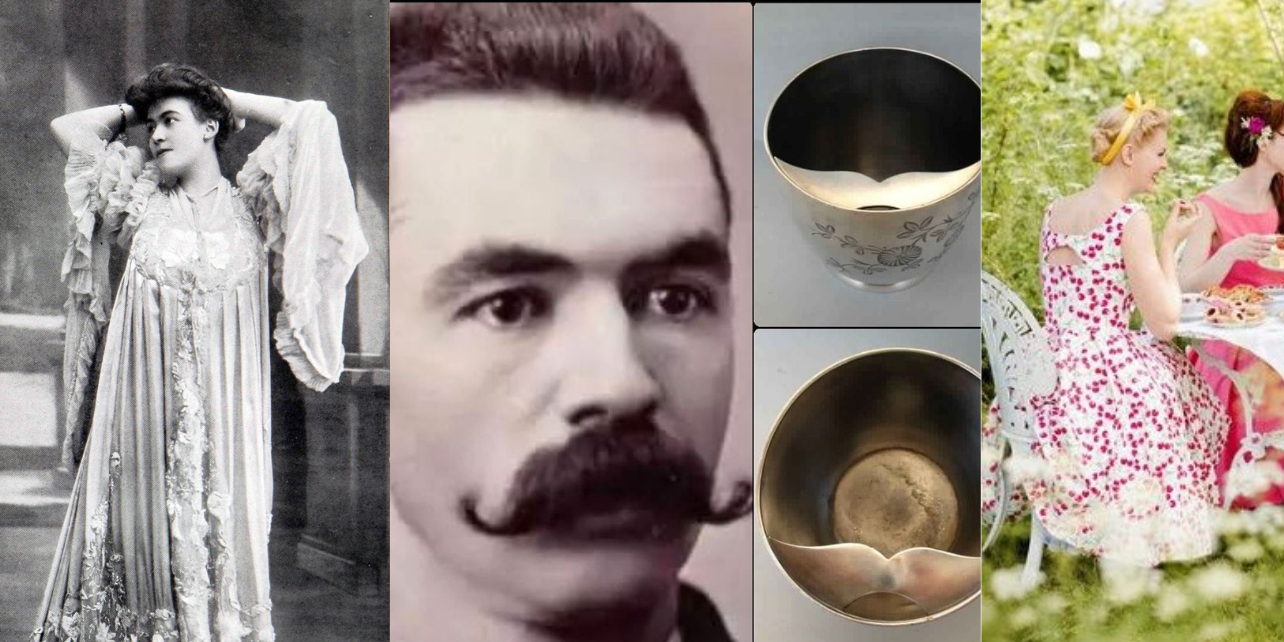

A Social History: What To Wear For Afternoon Tea

By the late Victorian period, afternoon tea parties had become a very popular occupation. Having started out as a spontaneous brainchild of the 7th Duchess of Bedford to ward off her mid-afternoon hunger pangs, it had soon expanded to include her aristocratic friends following suit. Initially, it was a women’s social occupation while their spouses were at work, but soon, spurred on by Queen Victoria’s Buckingham Palace garden tea parties, Sunday afternoon tea parties became a social institution.

In polite society there were definite rules attached to organising an afternoon tea party. Invitations were sent out for an afternoon ‘At Home’. However, tea was never mentioned on the invitation as this was an expectation.

A slew of of afternoon etiquette books started to appear, written by aristocratic ladies. As well as instructions as to how the tea table should be laid out, directives for the servants, and suggested seasonal items to enjoy, these extended to the wearing of gloves for female guests.

For example, the 1885 book ‘Etiquette: What to Do, and How to Do It’ by Lady Constance Howard, explained that ladies intending to eat ices, cake or bread “should remove their gloves, but gloves can stay on if one is only drinking without eating.” Another helpful tip was given in ‘The Etiquette of Modern Society: A Guide to Good Manners in Every Possible Situation’ (1881), when the unnamed author points out to us that a thoughtful hostess should always provide biscuits with tea, since these can be eaten more easily than sandwiches without removing one’s gloves.

By the 1870’s, afternoon tea parties would foster a unique form of dress. Tea gowns became popular attire for women in the Victorian age. They were made of flimsy chiffon or fine silk, often trimmed with feathery lace, or softly draped velvet for the cooler months. Their fluid shape was strongly influenced by the Japanese kimono, which had been worn by Japanese women for many centuries to conduct their highly formalised tea ceremony.

However, this new form of attire brought with it a strict code of etiquette: a tea gown was only to be worn for entertaining guests in one’s own home and was on no account to be worn anywhere else, even for a visit to the home of a close female friend or family member. There was a rationale for this. During the era of tightly laced corsets and wire framed bustles, their unstructured lines and light, sometimes sheer, fabrics meant tea gowns could be worn without a restricting corset underneath, the resulting look of which was much more revealing than the usual demure fashions of the time.

But for some women the tea gown offered even greater freedoms than that of comfort. With no corset strings to lace up, there was no need for a maid to help the lady of the house in getting dressed. A woman could entertain in her private rooms and not require the services of her maid. So, at times the tea gown fashion would lead to other temptations apart from whatever sweet treats were served on the tea tray.

In other words, the lady of the house’s lovers were sometimes entertained, often with the tacit understanding of her own husband. One 1879 article described how, ‘Our London ladies, who a few years ago would have considered the idea appalling, calmly array themselves in the glorified dressing-robe known as a ‘tea-gown,’ and proceed to display themselves to the eyes of their admirers. The reason, perhaps, is not very far to seek. Certain adventurous dames, who determined, some years since, an invasion of man’s last stronghold, the smoking-room, arrayed themselves for conquest in bewitching robes de chambre.’

Being diaphanous and flowing, and worn without the need for stomach squeezing corsets, they were blissfully comfortable. which was perhaps the main reason why women loved wearing them.

But despite the risqué connotations, tea gowns had become a necessary part of a lady’s wardrobe. Fashion writers of the day declared that ‘no season’s outfit is considered complete without an assortment of tea gowns’.

Tea gowns are not to be confused with tea dresses, which became fashionable from the 1930s for afternoon tea outings and parties. With their full skirts and hemlines positioned anywhere between the knee and ankle, tea dresses have none of the risqué connotations of tea gowns, and unlike tea gowns, tea dresses have never really gone out of fashion. In the 21st century they have once again become popular for vintage and retro tea parties, remaining a gentle echo of an age when elegance was served alongside every cup.

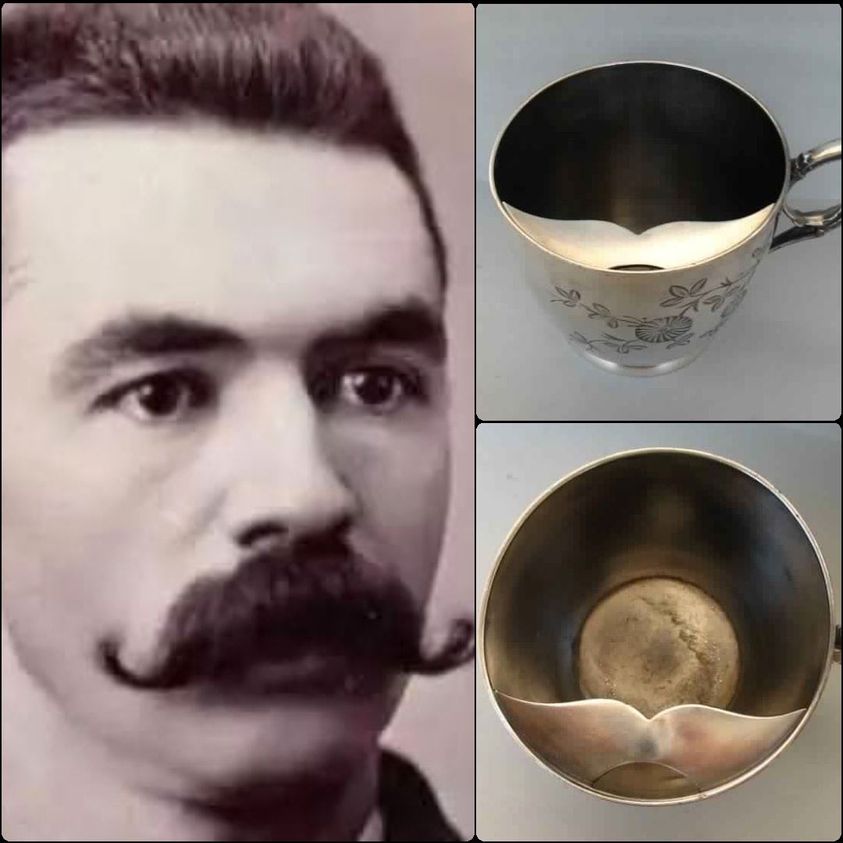

Victorian men also had an interesting tea-related fashion innovation. In the 19th century, men’s facial hair could be resplendent, especially their highly waxed moustaches. Consequently Victorian men had their own special cups for their tea drinking; these were called ‘Moustache’ cups. They had a small half-moon shaped ledge just inside the brim on which the drinker would rest his moustache so as not to get it wet (bedraggled was not a good look for a well-groomed moustache). The ledge had one semi-circular opening against the side of the cup through which the drinker could sip his tea. This ‘moustache guard’ also served another purpose. Wax was usually applied to a moustache to keep it fashionably stiff. When drinking hot liquids, steam from the drink could melt the wax, which would drip into the cup and give a rather nasty taste to the tea. The moustache guard helped to prevent this. Moustache cups went out of fashion by the 1930s as moustaches became trimmer and less florid, but not before movie audiences had seen Oliver Hardy announce in the first reel of the 1931 Laurel and Hardy comedy ‘Be Big!’ that he had already packed his moustache cup ready for a trip to Atlantic City.

Read more about the social history of Afternoon Tea with Gillian Perry MBE's new book - Please pass the scones: A social history of English afternoon tea. Find it on our shop here